For Ole Miss freshmen: My son William’s story

Published 7:03 am Sunday, August 28, 2016

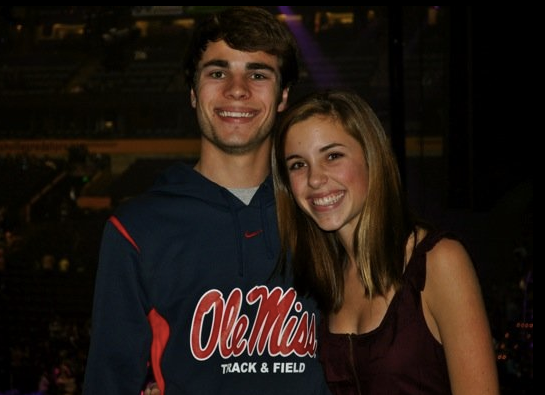

- The late William Magee and his sister Mary Halley Magee in 2010.

Update 8/15/17: A new center for alcohol and drug wellness education is being launched at Ole Miss. We need your help in making it a reality. You can read more about the William Magee Center for Wellness Education here and we hope you will contribute to help make it a reality.

A new freshman class started at Ole Miss this week and I wish I could tell them all this story.

It’s about my oldest son, William, who was a freshman in 2008. He would gladly tell them himself, if only he were alive.

With a quick wit and a big, friendly smile, William was an A student in the Honors College and Croft Institute at Ole Miss. He was fluent in Spanish, a member of Sigma Nu fraternity, and ran track for the Rebels his freshman and sophomore years.

The 400 hurdles is considered by many one of the most difficult in sports, and William had the courage to walk on and do it in the SEC. He lettered at Ole Miss his sophomore year and was rewarded by participation in the SEC Outdoor Track and Field Championships in 2010.

The Ole Miss letterman’s jacket he earned is one of our most prized possessions. That and the plaque he received for making the SEC’s all-academic team in 2010. It was quite an achievement considering he managed the Honors College, Croft Institute, fraternity, and track at the same time and came out on top.

“Making any kind of all-SEC team is a big deal,” I told him the year he worked to excel in track and academics for the Rebels. “It will be an achievement that will always mark who you are and what you can do.”

I still remember the pride in his voice the night he called me after receiving the plaque for the SEC academic honor on the floor of Ole Miss’ Tad Smith Coliseum during halftime of a Rebel basketball game.

“I was out there with the football players,” he said. “It was so cool.”

William met a beautiful, smart girl at Ole Miss who became his girlfriend for four years in college that we loved, and hoped that he would one day marry. He had friends who shared his joy of music and laughter and traveling the world. He was the same sweet, smart competitive young man who sang in the church choir and camped at Alpine in summers during his youth.

In college those first two years he appeared to be all-everything, and track practice kept him in check most weekdays his freshman and sophomore years. The season ran both fall and spring semesters with early morning weightlifting and afternoon workouts.

Enough to keep anybody straight.

On the weekends, when the music cranked up and the lights turned low, he partied, with so many other students.

It was all contextualized into a good collegiate reason as opposed to abuse or a problem. It’s the fraternity Christmas party, it’s Double Decker, it’s the night before the Alabama game, the Grove, a music festival. It was alcohol, it was ecstasy, marijuana, and Xanax, lots of Xanax.

We had talked before his freshman year at Ole Miss about the perils of viewing alcohol abuse and recreational drug use as something of a rite of passage in college.

“Some people get in so deep in college they can never get out of it,” I told him. “I’ve seen it happen too many times. Be careful.”

William suffered from anxiety and low self esteem. He tried to medicate with alcohol and drugs, like so many others. He was comforted that substances like alcohol brought him closer to the conversation in social situations. He was considered a square more than a partier, and William hid his habit from many friends, but privately drawing the line was hard and one drug led to another over time as so often happens, sometimes by accident.

I had warned him that drug dealers can’t be trusted, that drug dealers know tricks, like mixing heroin with cocaine to make it doubly addictive before a user knows what hit them. And it is easier to succumb when the dealer is a fraternity brother or the guy down the hall at the dorm who looks a lot like you.

“I know,” he said, brushing off my warning. “Everybody knows that.”

William was a senior at Ole Miss by the time we recognized the depths of his troubles. He graduated, another proud moment, but he was frail. He had wanted to go to law school but instead checked into rehabilitation once he realized the addiction had advanced to the point that he was no longer the person he once was.

William was scared. The drugs had taken over.

Dropping our firstborn off at a rehabilitation facility that cool fall day wasn’t easy. We hoped the 30-day stay in an inpatient treatment center would get this problem under control and his life back on track, then we could all get back to normal.

We were naïve, or maybe just hopeful, as parents tend to be.

William bounced between several rehabilitation facilities around the country for the next year. He was kicked out of one in Colorado because he purchased a bottle of cough syrup from a drugstore and drank it to get high.

He was kicked out of another because he and a friend found a way to purchase one pain killer pill each from the outside world. They took it, for old times sake, and William confessed the misdeed to the counselor, asking for another chance, thinking his admission might make a difference.

“You were right,” William told me. “My plan was to graduate (from Ole Miss) and quit. But it’s harder (to quit) than I thought. I’m not sure how to get out of this.”

We got William back into a rehab facility in Nashville, and finally, progress. He graduated to a halfway house. With a college degree, he got a job at a Mac computer store. They put him in charge of training. His coworkers bragged about his sales skills and said he was a joy to work with.

“Sweetest young man,” they said.

Yes, and so very smart.

I quit my job and took another to be closer to him, visiting weekly and having daily phone conversations, anything to try and help. So I was alarmed one Friday night when I kept calling and he did not answer. By the next morning, when he still did not answer, I knew.

The drive to Nashville took two hours but it felt like 22. I could not feel my hands on the wheel and my stomach churned. Once there, I found him dead from an accidental drug overdose.

William had gotten off work that Friday and gone to a Widespread Panic concert, where he ingested alcohol and most every drug imaginable for hours. When he got home from the concert he texted a dealer and bought more drugs.

That cocaine, ingested just before midnight, combined with the other drugs in his system and took his life. The body can only take so much, after all. Eventually, it shuts down.

Three years plus a few months later we have made peace with William’s addiction and tragic death, as much as parents can. We were blessed beyond measure to have been given this son to have in our lives for 23 years. Blessed beyond measure. And that is enough.

We have memories of laughter and warm hugs, plus a hard-earned letter jacket from Ole Miss and so much more to cling to.

But we don’t want other students to suffer like he did, or other families to suffer like we have. That’s why I wish I could reach out and touch every freshman to tell them William’s story, to tell them that alcohol and drug binging and abuse isn’t a collegiate rite of passage, or a contextual excuse.

It can be a dangerous if not deadly path that is hard to escape.

David Magee is Publisher of The Oxford Eagle. He can be reached at david.magee@oxfordeage.com.