Mississippi plagued by high rent, low wages

Published 6:00 am Sunday, July 31, 2016

By R.L. Nave

Mississippi Today

A phalanx of local and state officials cut the ceremonial ribbon at East Village Estates, an affordable housing development in the shadow of the Jackson Medical Mall, in May.

Developers broke ground on the project, made up of 44 town homes built with financing from the federal low-income housing tax credit program, in December 2013. Also in the works are plans to expand the development as well as build another 88 town homes near downtown Jackson.

Despite recent efforts, advocates say, approximately 286,000 Mississippians still have unmet housing needs. The state of Mississippi is facing an affordable housing crisis, the causes of which are multifaceted.

Phil Eide, a senior vice president at Hope Enterprise Corp., a Mississippi-based financial services nonprofit organization, says there is both a shortage of good-paying jobs in the state as well as affordable quality homes for people to rent and buy.

“Overall, it’s bleak and it has been bleak for very low income families that are trying to eke out a living,” Eide said.

Mississippi not alone

Mississippi’s challenges reflect a broader national trend, according to Out of Reach, a new report from the Washington, D.C.-based National Low Income Housing Coalition. The report shows that nationally a renter must earn $20.30 an hour to afford a two-bedroom apartment; $16.35 per hour for a one-bedroom unit.

Another way to look at it, the report’s authors write, is that a person making the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour (which is also the state minimum wage in Mississippi) would need to have almost three full time jobs or work approximately 112 hours per week all year long to afford a two-bedroom at fair market rent.

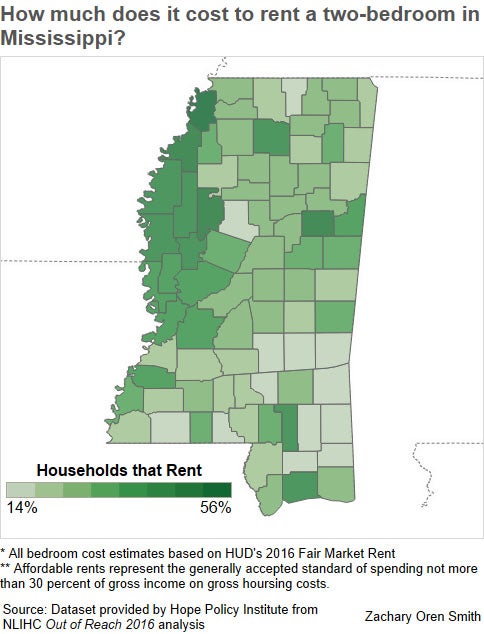

In Mississippi, approximately 31 percent of households are made up of renters, who earn a mean wage of $10.64 per hour. Here, renters have to work 78 hours every week to afford a fair-market rent of $732 per month for two-bedroom housing.

Scott Spivey, executive director of the Mississippi Home Corp., a quasi-governmental agency that administers financing for affordable housing programs, said the fact that rents have exceeded wages make it hard for families to pay their rent every month and put some cash aside for emergencies.

“A lot of families in Mississippi, housing costs are so high that a sick child or broken arm is the difference between being able to pay or not pay bills that month,” Spivey said.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that housing is considered affordable if it’s less than 30 percent of wages. Spending more than that means housing is increasingly unaffordable because it starts eating into other household expenses such as groceries and health care.

Compounding the problem in Mississippi is the 6 percent rate of unemployment, 44th among the states, as of April 2016, according to seasonally adjusted Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The combination of high unemployment and low wages for Mississippians struggling to pay rent creates myriad quality-of-life issues, said Hope’s Phil Eide.

“How much time do we expect people to be away from their homes and not be with their families?” Eide asked.

Oxford company finding answers

Clarence Chapman, president of Oxford-based Chartre Consulting, which developed the East Village Estates in Jackson and several others around the state, said his projects are designed around improving the quality of life for residents by providing safe, stable neighborhoods in addition to family support services.

“In order to rebuild your communities, you have to rebuild your people … and you do that around your homes,” Chapman said.

Chartre and other developers build homes with low-income housing tax credits. Currently, 12 such projects are ongoing in Mississippi. The Internal Revenue Service provides Mississippi with $6.8 million in tax credits to award each year. Developers apply to the state for the credits, which investors purchase to offset their federal tax bills over 10 years, which subsidizes the cost of the housing project.

Affordable housing shortage

Federal officials point to the housing tax credit program, the federal Section 8 program and other federal initiatives as examples of the private and government sectors working together to solve the affordable housing shortage, which includes a $26 billion backlog for public-housing renovations.

Doris Franklin, executive director of Christian Housing Development Corp. in Columbus, said many families there are trapped in older housing because there aren’t enough new homes being built.

“There’s a lot of existing housing, older housing that families are taking as the last resort,” she said. “There’s very little building going on and a lot of rentals. People are continuing to rent because it’s easier.”

Some relief could come from an injection of cash for federal housing tax credits. Last week, U.S. Sens. Maria Cantwell, D-Washington, and Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, introduced legislation to increase the amount of tax credits states receive by 50 percent in the next five years by sweeping unused funds from other tax credit programs.

Mississippi officials and housing advocates say they plan to lobby the state’s congressional delegation to support the bill.