Cuts may swell county jails with mentally ill

Published 12:00 pm Monday, August 8, 2016

By R.L. Nave and Patsy R. Brumfield

Mississippi Today

Bill Walker’s family nightmare began over July 4th weekend five years ago, when his 19-year-old son, Reynolds, went missing after a party with friends outside Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Days later, the former Washington School High School track star was near Clarksdale on his way home to Greenville when a trooper arrested him, barefoot, with no wallet and no cell phone.

Bill Walker and a friend drove up Highway 61, and bailed his son out. On the trip back, Walker recalls Reynolds kept turning up the radio volume and saying he heard voices giving him instructions.

“He said he heard (President) Obama telling him he was going to be a DJ in Los Angeles or New York and be his drug czar,” Walker recalls. “When the police took off after him, he said he thought it was an official escort to the airport.”

Across the years, after multiple efforts to get his son into long-term treatment, Bill Walker said they know Reynolds is psychotic, bipolar and delusional. Some short-term therapies appeared to be successful, then Reynolds would refuse to continue medication and the behavioral cycle would start again, he said.

Desperate for a solution, Walker said he purposely goaded Reynolds into an argument while they were in Starkville, which led to his son striking out at him. That put Reynolds in the Oktibbeha County jail, where he’s been since April, held without medical intervention.

Bill Walker says he has been trying to work with the system, but is unsure whether his son will find in-house treatment in a financially challenged state facility.

“Now he’s sitting there rapidly deteriorating — and this is about a budget issue,” Walker said with anger in his voice. “It’s so stupid.”

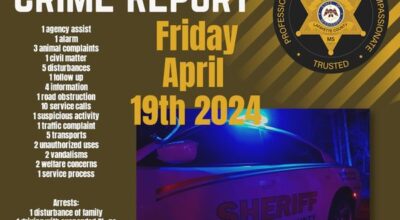

Oktibbeha County Sheriff Steve Gladney says Reynolds Walker is an example of the challenges facing criminal justice officials grappling with mental illness issues in local courts and jails.

“We have to hold them until there’s a bed available” at the state hospital … “but jail is not where these people should be,” Gladney said. “I feel bad that I can’t do more to help them.”

Jails not equipped

Budget issues that keep people in jails and prisons without needed mental-health treatment are not new. However, local law enforcement officials, judges and advocates say they fear that the latest round of state mental-health department cuts could put even more mentally ill people behind bars when they should receive medical help instead.

Mental-health funding has been in sharp focus since the end of the 2016 legislative session, when the Department of Mental Health saw its funding cut by $8.3 million, or 4.4 percent, prompting the agency to eliminate more than 100 beds at Mississippi State Hospital, East Mississippi State Hospital and South Mississippi State Hospital.

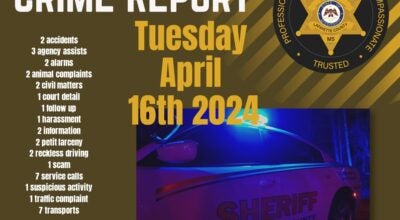

K.C. Hamp, Tunica County sheriff and president of the Mississippi Sheriffs’ Association, said his members are worried about the mental-health cuts trickling down and affecting people his deputies encounter every day.

“The cuts will affect every county across the state and affect adequate care and treatment for people with those illnesses,” Hamp said. “Local county sheriffs are not equipped to handle people with these conditions.”

Joi Owens, managing attorney for Disability Rights Mississippi, which is involved in several cases in which people with disabilities are suing to gain access to services, said people with mental illness already are criminalized inappropriately and do not receive the services they need when incarcerated.

“Mental-health services and supports, especially those which are community-based to maximize independence and stability, need to be expanded throughout the state,” Owens said. “Cuts to already inadequate mental-health services are likely to add more pressure to the criminal justice system rather than improving the quality and variety of services available.”

A 2010 report from the Treatment Advocacy Center and National Sheriffs Association, both headquartered in Virginia, found that three times more seriously mentally ill people were in jail than in hospitals. Those findings are bolstered by a study published last month from Treatment Advocacy Center and Washington, D.C.-based Public Citizen that involved surveys of jail personnel in 39 states, including Mississippi.

Almost 76 percent of respondents reported “seeing more or far more inmates with serious mental illnesses, compared to five to 10 years ago.” Several jail officials who are not named in the report cited budget constraints as contributing to the problem.

One official whom surveyors did not identify wrote that the increase of mentally ill inmates in a small jail had been a cause for alarm for the staff, which now had to deal with the problems without the help of medical professionals because of budget cuts.

Adam Moore, a Mississippi mental-health department spokesman, said the recent reductions mainly affect adult male chemical-dependency units at Mississippi State Hospital and East Mississippi State Hospital.

“DMH program directors made the decision to close those programs for two reasons: 1) Since 2008, DMH has closed 500 psychiatric beds throughout the state. 2) Other chemical dependency treatment service options are available in the community through DMH Certified Providers,” Moore told Mississippi Today in an email.

State budget writers have said cuts were necessary to balance the books in the face of less than expected revenues. In a June interview with Mississippi Today, Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves specifically questioned the efficacy of some mental-health department program costs.

Referring to the Department of Mental Health, Reeves said: “The program they’re shutting down, 750 patients they had last year, how many of those have repeated a similar program either in the Department of Mental Health or outside the Department of Mental Health? That seems like a reasonable question. I asked it. The answer was: We have no idea. So we spent $3.8 million on a program at Whitfield and East Mississippi — a program that’s needed, by the way — and we have no clue and they can’t tell me if it was successful or not. They can’t tell me if it helped one patient.”

When the Legislature met recently in a special session to fill budget gaps, House Democrats unsuccessfully tried to reinstate some funding for mental-health services.

“This body has made some very serious mistakes,” Rep. Adrienne Wooten, D-Ridgeland, told colleagues during debate on two amendments she offered to move money back to mental-health services.

The backlog of those needing mental health services is acutely felt in local courts and jails. Troy Peterson is the Harrison County sheriff and oversees the state’s largest jail, which can hold 750 prisoners. Peterson said while prisoners receive treatment from psychiatrists, Harrison County’s first responders lack places to take people with mental illnesses besides jail.

“The jail is not someplace I feel the mentally ill should be housed,” Peterson said.

Yet that’s often where those with mental illnesses end up. The Clarion-Ledger reported earlier this year that a man named Steven Jessie Harris spent 11 years in the Clay County Jail waiting on a mental-health evaluation. In 2013, a prisoner at the Raymond Detention Center named Larry David McLaurin was beaten to death, allegedly by his cellmate, Elton Oneal McClaurin; both men had mental-health issues.

In May, the U.S. Justice Department announced a settlement with Mississippi’s most populous county over conditions at its jail, where the Justice Department said “prisoners with mental illness are acutely harmed” by jail conditions. The agreement has been heralded for addressing mental illness at the Hinds County jail. However, with the latest state budget cuts many officials say a question mark hangs over the proposed reforms.

Tomie Green, the senior circuit judge in Hinds County, who worked in the health-care field in the late 1970s and early 1980s before going to law school, estimates that anywhere from 30 to 40 percent of the criminal defendants who face her struggle with some form of mental illness. Piling on additional cuts to mental-health “is almost inhumane,” she said.

“It’s going to make the job harder, but it’s going to make the community less safe,” Green said. “Without programs and places for people to go, they’re going to end up in our neighborhoods.”

‘Slow torture’

Today, Reynolds Walker, now 24, sits alone in an Oktibbeha County Jail cell, waiting for a Mississippi State Hospital bed to treat the mental illness that overtook him with vicious suddenness five years ago. Dozens of other inmates await a psychiatric evaluation to determine their competency to stand trial.

The Mississippi State Hospital at Whitfield has 35 forensic-unit beds available for defendants with court-ordered commitments. Fifteen of those beds are for inpatient evaluation, treatment and competency restoration for people charged with crimes. For those 35 beds, 144 names are on the waiting list with an average wait time of about 11 months. Staffing the unit are one psychiatrist and one psychologist to treat mentally ill criminal defendants from all 82 counties.

Mississippi State Hospital’s proposal for a new 60-bed forensics facility, which can help local law enforcement move mentally ill inmates toward treatment, projects the cost at about $17.5 million. Completion of such a facility would be “a significant factor” in breaking the logjam from county jails to treatment, officials repeatedly have told legislators.

The Department of Mental Health did not reduce the number of forensic beds, but agency officials recognize the need for more.

Mississippi State Hospital spokesman Mike Christensen acknowledges that the facility’s ability to help families like the Walkers is far short of what’s needed, but state budget pressures have consequences.

“Our records show that as far back as 2002, MSH requested funding for renovations for the Forensics Unit,” Christensen notes. “Beginning in 2008, the request began for funds for a new unit to replace the existing facility, which was built in 1955.”

An attorney, Bill Walker says it’s time for drastic measures — possibly a federal lawsuit to force appropriate funding to help his son and other Mississippians and their families in similar distress. To force inpatient treatment for his son, Walker sees little choice but to file legal action against the state for failing his son and others in similar situations.

“Reynolds has me to fight for him, but there are so many people in Mississippi who don’t have anyone like that,” he said.

“This is such a cruel punishment, there’s no help without his being committed (to Mississippi State Hospital),” Walker said. “I don’t know if he’s retrievable. The state is slowly torturing him and my fear is that he will be like this forever.”