Meet Joshua Horton: Ole Miss law student overcomes odds, fights to make difference

Published 6:30 am Sunday, October 30, 2016

- (twitter)

This is a story you won’t be able to forget.

About a man whose name you will want to try and remember.

Joshua Horton is a second-year Ole Miss Law School student who finished Magna Cum Laude from the Ole Miss Honors College. He is determined to make your world a better place, and lives better for many individuals who are in the worst kind of struggle.

But not too many years ago Horton was your worst nightmare, a person with substance abuse disorder who could not stay sober or out of jail.

When Horton drank, which was every day, he never knew where it would end, waking up with no recollection of the night before, either on a bed, or in a jail cell.

“The addict never knows where it will stop,” he says.

Living in the Atlanta area at the time, Horton took fistfuls of Xanax with alcohol, sometimes dozens of pills in a day, and should have died so many times he literally can’t remember them all.

He had a rap sheet so long that police and others had little respect. He had grown up around addiction, got drunk as a young man and married an addict (it didn’t last long), and didn’t really know any other way.

Now in his early 30s, police picked up Horton in Alpharetta, Georgia in 2008 after he repeatedly fired a 9mm handgun wildly inside his townhouse while drunk. When police arrived Horton after neighbors made a call, he had moved outside and thrown the gun in the bushes.

Horton gave the swat team the bird while swearing at them and went for a beer in his truck. Law enforcement officers followed him with weapons, thinking he was reaching for a gun, and “would have had every right to shoot me dead.”

“Incoherent,” he says.

Nobody was hurt but Horton landed charges including possession of a firearm by a convicted felon, 13 counts of reckless conduct, 13 counts of discharge of a weapon near a public highway, and terroristic acts and discharge while under the influence.

He went to his first court appearance chained to another man while still sobering up. He had no legal representation. A young, female African-American judge for no explicable reason looked at Horton and said, “I see something in you son” after reading the long list of charges.

The judge ultimately threw out all felonies and Horton was convicted of just one misdemeanor of discharging a firearm while under the influence.

“She changed my life that day,” Horton recalls. “She taught me mercy.”

He plans on finding her after law school graduation to explain how she altered the course of his life that day.

Horton was a high school dropout who took the GED while drunk, and passed. He had more than 20 substance related convictions in all, but ended up at Itawamba Community College in Fulton as an adult student because he had nowhere else to go and figured there had to be a better path.

He made good grades but was still drinking, though not as aggressively. Two school administrators took Horton on as caring mentors, loving him until he could learn to love himself and start the journey of recovery from substance use disorder.

It worked.

Horton got sober and began to soar. He learned he was not a moral failure but suffered from a disorder that affects millions of Americans, yet remains so stigmatized by society that it keeps addicts silent and ultimately kills them. He got a scholarship to Ole Miss and ended up in the Honors College, even though nobody at the University really knew how deep and far his rap sheet ran when they took him in.

Heads turned once they found out, but the support for Horton continued, grew even, and he thrived, graduating after writing a thesis on rehabilitation vs. incarceration for non-violent substance abuse offenders.

Horton’s road from inmate to advocate was being paved.

But undergraduate school is one thing; law school with an arrest and conviction record like that is another, since state bar associations don’t usually admit people with long rap sheets.

Horton decided to stay to attend Ole Miss Law School, however, and found similar support. Now in his second year, Horton works as an intern at Rayburn Coghlan law office in Oxford and with his non-profit Southern Recovery Advocacy based out of Oxford in his spare time.

He also volunteers and helps with individuals in Lafayette County Drug Court and the local treatment center Haven House, and is involved with fellow advocates in the recovery movement. Earlier this year Horton was part of a small group that met with Mississippi new Prison Commissioner Marshall Fisher and national leader in the recovery movement John Shinholser to discuss bringing real recovery into prisons and communities in the state.

He also just received an internship with the Bronx Defenders, which is one of the top Defense Program internships in the country with the help of Tucker Carrington, who is the head of the Mississippi Innocence Project, which has exonerated several men wrongfully condemned to death.

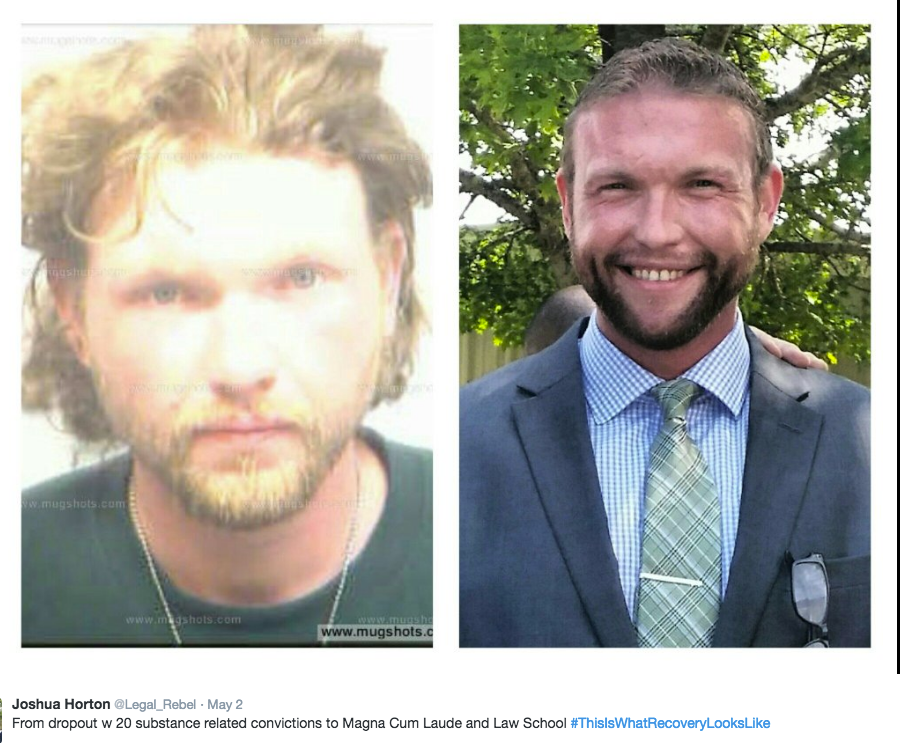

Horton’s Twitter handle is @Legal_Rebel and last spring he posted the tweet, “From dropout w 20 substance related convictions to Magna Cum Laude and Law School #ThisIsWhatRecoveryLooksLike.”

The tweet was accompanied by two photos: one of Horton in a mug shot with a scruffy, drunken outlaw appearance, and another of him wearing a suit and tie and smiling broadly as an Ole Miss law student.

He’s passionate that addiction can be treated and that many suffering humans could be more beneficial to society and themselves with support rather than incarceration. He wants better options for treatment and care on college campuses, and believes state governments can do more in communities rather than just writing arrested addicts off as criminals.

“My recovery teaches me that my dark past is the greatest asset I have,” Horton says. “With it we can avert death and misery for others. It’s quite the paradox.”

Horton plans to do something about it all with that law degree he is scheduled to earn a semester early from Ole Miss a next year, devoting his life in the legal profession to recovery advocacy. He’s concerned that substance abuse has now become the number one cause of death for young people, and that addicts of all ages need someone fighting to help them get to recovery.

It won’t be glamorous legal work, but Horton understands better than others that somebody needs to do it.

And nobody is better prepared than he is.

David Magee is Publisher of The Oxford Eagle. He can be reached at david.magee@oxfordeagle.com.