Removal of Confederate monuments in New Orleans a powerful example for Mississippi to follow

Published 9:04 am Wednesday, May 3, 2017

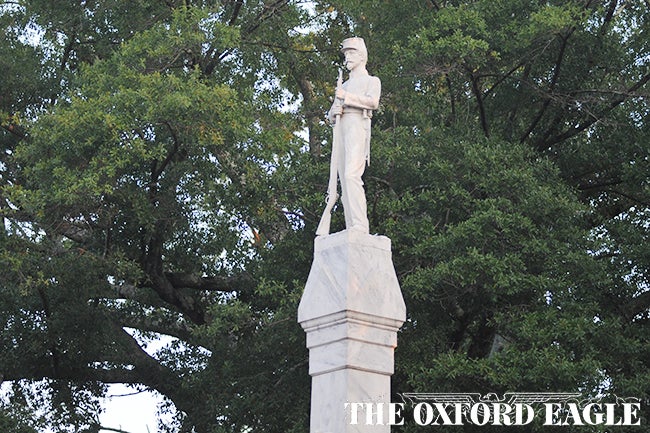

- A confederate statue is located in front of the Lafayette County Courthouse, in Oxford, Miss. on Thursday, September 3, 2015.

New Orleans has placed itself on the frontlines of an ongoing battle over where Confederate memorials belong in the modern-day South with the removal of four prominently placed monuments, a controversial process that began last week.

Since 2015, Mayor Mitch Landrieu (D) has actively led the effort to have the statues removed based on a sole purpose: The monuments don’t represent the city of New Orleans and what it hopes to become. While some have accused Landrieu of trying to “erase history,” the mayor’s efforts include storing the dismantled statues until they can be relocated to museums or other places of historical context.

“That’s different from telling the people of the city of New Orleans that they have to keep them on property owned by the people of the city of New Orleans,” Landrieu told the Washington Post last week. In other words, monuments honoring the Confederacy, a traitor nation that battled the United States to maintain the institution of slavery, have no place on public, taxpayer-funded property.

The fight to protect Confederate symbols is rarely accompanied by efforts to contextualize their historical significance, an odd absence for an argument often based on remembrance of the past. More often than not, it serves as a vehicle to perpetuate the idea that no one understands the Confederate cause except those who continue to revere it with emotionally charged ideas of heritage and tradition while conveniently omitting the ugliness of slavery and its social and economic role in the antebellum South.

Oxford is certainly familiar with this narrative. Even as one of the more progressive towns in Mississippi, it’s hard to ignore that two of the most prominent and heavily trafficked locations in town—the Lafayette County Courthouse and the Circle at the University of Mississippi—each house a Confederate monument erected in the early 1900s. It’s undeniable the town and university have transformed in recent years to distance Oxford from a past marred by race-related conflict. Mascots have been replaced. Songs silenced. Streets renamed. Flags furled.

There is one thing most should agree upon: No one should ever forget what the Confederacy fought for and Mississippi’s role in that war. Flags and statues don’t tell that story, at least not entirely. And truth be told, anyone fighting to preserve those symbols as modern-day representations of who we are should be just as passionate about displaying Mississippi’s Declaration of Secession, a summary of the causes that fueled our state’s doomed fight:

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product, which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution, and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin…”

Put those words on a stone slab in front of the courthouse in the name of historical preservation because that is the message sent to the world when these symbols stand without context or consideration for what they mean to everyone, not just descendants of Confederate soldiers.

Symbolic reverence, whether through flags, songs, mascots or monuments, represents who we are as a community and state. More importantly, it represents what we want the world to know about us and what we hold sacred. Remnants of the Confederacy should serve to educate the world about what our state was, not define what it is.

New Orleans understands that. It’s time for Mississippi to follow suit.