Chickasaw leader Piominko impacted US, Mississippi history

Published 9:54 am Monday, September 11, 2017

By M. Scott Morris

AP News Exchange

BALDWYN, Miss. (AP) — One of George Washington’s friends used to live in Northeast Mississippi.

“George Washington called Piominko his friend in his letters,” said Mitch Caver, 58, of Baldwyn. “Piominko did the same in return.”

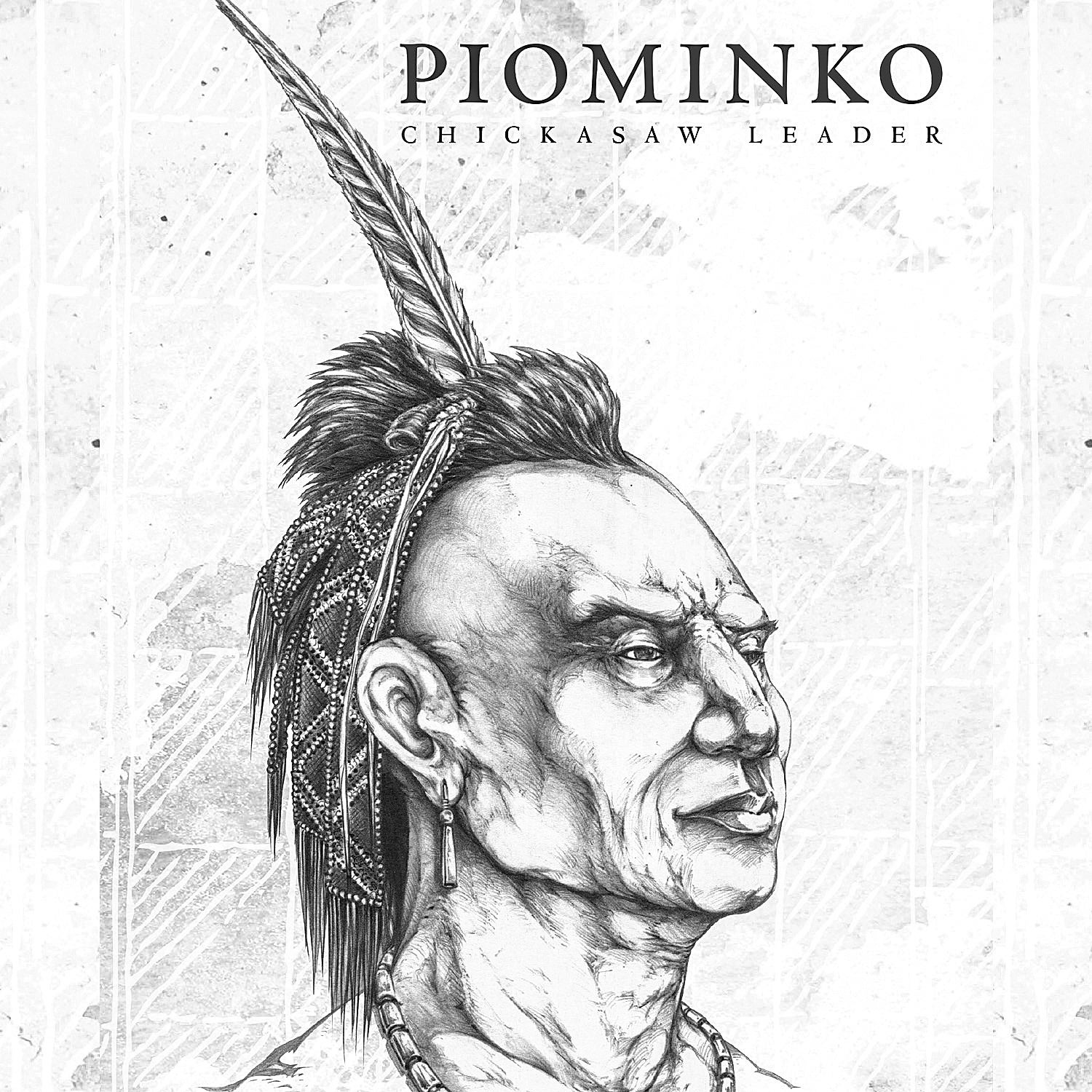

Area residents know him as Piomingo, but the book Caver and Thomas Cowger co-wrote is titled “Piominko: Chickasaw Leader.”

According to the book, his name was written a variety of ways, including Paimingo, Opiamingo, Opia Mingo, Pyo Mingo, Opoiaming and Opaya Mingo.

“‘Minko’ means leader. It was a title,” Cowger said. “We don’t actually know what his real name was. European leaders heard something similar to that, so that’s what we use today.”

Cowger is a professor of history at East Central University in Ada, Oklahoma, where the Chickasaw Nation has its headquarters. He’s also director of the university’s Native American Studies Program and the Chickasaw endowed chair.

In 2013, he brought a bunch of students to Tupelo and Lee County, so they could explore the Chickasaw homeland. That also was the first face-to-face meeting between Cowger and Caver, though they’d worked together on other projects.

“I had brought what I knew about Piominko,” said Caver, who developed a fascination for Chickasaw history as a child.

The pair decided to collaborate on the book, which was released in May by Chickasaw Press.

The authors had significant obstacles to overcome before they could share the story. For one, Chickasaw wasn’t a written language during Piominko’s time.

“It was also a challenge because there was no oral tradition,” Cowger said. “When we got started doing this, we were somewhat overwhelmed.”

If Piominko was a significant figure only in Chickasaw history, that might’ve put an end to their efforts. But the man also was integral to U.S. and Mississippi history.

“He was well known across the country from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico at the time,” Caver said. “He was called ‘Our Friend Piominko,’ ‘The Great Piominko.’ Those were the words used.”

As the authors learned more about their subject, he continued to impress them, especially considering his humble beginnings. His father died before he was born.

“It’s a rags to riches story,” Cowger said. “He grew up with a single mother.”

For part of his early life, he was raised among the Cherokee, where he developed relationships that helped him avoid conflicts after he became a Chickasaw leader.

European Americans often referred to him as Mountain Leader, and a map from the 1790s that’s included in the book shows “Mountain Leader Trace,” a route Piominko traveled when dealing with U.S. government officials in Tennessee.

“After his death, it was called the Natchez Trace,” Caver said. “Before that, it was called Mountain Leader Trace and it was centered in Tupelo.”

When the United States of America was young, its future was in doubt, and Spain was a major competitor.

In 1797, a meeting was arranged between the United States and the Chickasaws around the area that became Memphis. Piominko represented the pro-American faction, while a rival chief, Wolf’s Friend, invited the Spanish to the gathering.

“It must have been an awkward meeting having both Americans and Spanish there in what turned into a contentious discussion to determine what nation the Chickasaws would ally with,” Caver said. “Finally, Piominko won the argument and Spain that day lost all hope of any control of Tennessee or Northern Mississippi.”

Piominko never wavered from his decision, even though the U.S. government didn’t always live up to its side of the bargain, Cowger said.

“One thing people forget is just how close Spain came to controlling the southeast and Mississippi,” Cowger said.

It’s no wonder Washington recognized the importance of Piominko in his letters. According to an account from John Quincy Adams’ diary, the two leaders sat together and shared “a large East Indian pipe” that Washington had arranged to have.

“Whether this ceremony is really of Indian origin, as is generally supposed, I confess I have some doubt,” Adams wrote. “At least these Indians appeared to be quite unused to it, and from the manner of going through it, looked as if they were submitting to a process in compliance with our custom.”

For such an important man in history, there aren’t many images of Piominko and none that can be traced to him without some shred of doubt. But Caver followed clues to a private collection in New Hampshire, where he inspected a ship’s figurehead carved to resemble a Native American.

Scholars have tied the figurehead to other tribes, but there are possible connections to the Chickasaws. Its style of dress is similar to that described by a Presbyterian missionary who visited the Chickasaws in 1800.

In addition, the statue is standing next to a dog. Ofi Tohbi is a legendary white dog and considered to be a loyal guide and protector of the Chickasaws.

Caver also found an article that first appeared in an English newspaper in 1794 and was reprinted later that same year in the Philadelphia Gazette:

“The William Penn, now lying at Iron-gate Stairs, is allowed to be the finest American vessel that ever appeared in the River; She is built entirely of cedar, and carries 300 tons. The figure of the Indian and his dog on her head, is said to be an exact representation of Piamingo, Chief of the Chickasaws, now living. As she was the first vessel that ever he saw, he attended the building of her from the moment her keel was laid, till she was launched; and the moment he saw her descend to the waves set up the most dismal howl, which was immediately succeeded by the most immoderate transports of joy, when he saw that she did not sink.”

Caver had no difficulty imagining the William Penn sailing into a foreign port with the U.S. flag flying high and the figurehead out front.

“It’s a symbol of liberty, of freedom,” he said.

With “Piominko: Chickasaw Leader,” the authors sought to discover and report as much as they could about a man from Northeast Mississippi who helped shape world affairs. Along the way, they found someone worthy of their respect and admiration.

“You see very few people in history who are shining stars who rise up at the right place and the right time,” Cowger said. “Piominko was one of those leaders.”