Ole Miss unveils new contextualization plaques

Published 3:30 pm Friday, March 2, 2018

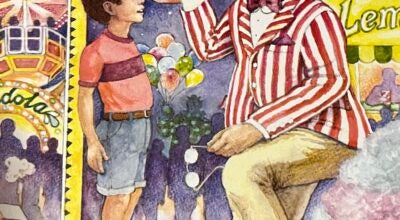

- Don Barrett looks over a window dedicated to the University Greys at Ventress Hall at the University of Mississippi, in Oxford, Miss. on Friday, March 2, 2018. The university unveiled history and context plaques for university buildings such as Barnard Observatory, Lamar Hall, Longstreet Hall, George Hall, as well as a plaque recognizing the university’s enslaved laborers in the construction of Barnard Observatory, the Old Chapel (now Croft), the Lyceum, and Hilgard Cut, and the stained-glass Tiffany windows in Ventress Hall recognizing the University Greys, who were students who fought in the Civil War. (Bruce Newman, Oxford Eagle via AP)

The University of Mississippi unveiled six history and context plaques on Friday, following months of discussion from the Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on History and Context and feedback from stakeholders.

The plaques are located in various locations around campus as part of Chancellor Jeff Vitter’s commitment to item five of the University’s 2014 action plan.

According to the plan, the plaques “offer more history, putting the past into context” and do so “without attempts to erase history, even some difficult history.”

The plaques are located at Longstreet Hall, George Hall, Lamar Hall, Barnard Observatory, the Tiffany stained glass window inside Ventress Hall honoring the University Greys and a more central plaque acknowledging the enslaved persons who built and maintained the university.

Vitter said the plaques are the product of a “deliberate, thoughtful and academically focused endeavor.”

“As Mississippi’s flagship university, we have long been committed to honest and open dialogue about our history,” Vitter said. “We are here today to recognize that this work indeed is a significant moment of change and transformation in the life of our university, and we’re here to honor this moment by sharing our story broadly, and in a forthright manner.”

The plaques each provide background information on the lives of the people the structures commemorate.

For example, the plaque in front of Barnard Observatory commemorates the actions of Frederick A.P. Barnard, the University’s third chancellor. Barnard, credited with the 1859 construction of his namesake observatory built with slave labor, was “enmeshed in a significant controversy involving slavery.”

One of Barnard’s slaves, Jane, was sexually assaulted by a student at Ole Miss. After telling Barnard’s wife and having her story verified by a professor, Barnard expelled the student and refused his readmittance. At the time, taking the word of a slave over a white person was a violation of state law, and the state legislature launched an investigation against Barnard, ultimately leading to his departure in 1861.

CACHC Co-Chair Dr. Don Cole, assistant provost and associate professor of mathematics, says the committee’s work was a difficult task, but he is proud to have been part of it.

“It’s not always easy to talk about. Emotions and feelings are involved,” Cole said. “These are the types of issues we’re supposed to take on. We’re the first institution in the state to do so, one of the first in the nation to do so, and many others will follow our path.”

One story that was particularly difficult to discuss is rendered on the plaque in front of George Hall, detailing the work of James Zachariah George.

George served terms as chairman of Mississippi’s Democratic Executive Committee, a member of the state’s supreme court and a U.S. senator. However, he is most notable for crafting the “Mississippi Plan,” a system of voter intimidation and repression aimed at returning the state to all-white Democratic rule, in 1875. He was also instrumental in rewriting the state constitution in 1890, which reduced the number of eligible African-American voters from 147,205 to 8,615. African-Americans in Mississippi did not receive full voting rights until the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965.

Vitter said the CACHC’s work is not complete yet and detailed several changes that will come in the next few years.

“In addition to the six contextualization plaques, we have the remaining tasks to finalize,” he said. “We have the University Cemetery and a related memorial, which we will be adding individual gravestones to recognize the sacrifice of each person known to be buried there, as well as a marker in an appropriate location to recognize the African-American men from Lafayette County, who served in the Civil War in what was, at the time, called the U.S. Colored Troops.”

In addition to the markers at the cemetery, Vitter detailed plans to clarify that Johnson Commons is named after Paul B. Johnson, Sr. by adding the designation to the building’s signage. He also confirmed that Vardaman Hall will be renamed once renovations are complete “in a few years.”

Dr. John Neff, director of the Center for Civil War Research, provided context for this decision in his keynote address, in which he explained that the university and community surrounding it are the “sum of decisions,” both good and bad.

“By contextualizing these important aspects of our campus, we emphasize the distance we have traveled between our time and theirs,” Neff said. “Keep in mind, less than a century ago, individuals at the university proudly placed on one of our buildings the name of a man, a virulent racist, who once advocated to his white voters that if necessary, he would lynch every black man and woman in this state.”

Both Vitter and Neff say the unveiling of the six plaques is the first step in a long journey, and there is still a long way to go in terms of contextualizing certain aspects of the campus and its forebears.

However, Neff said it is important to incorporate both history and memory to understand whether past decisions, which at one time all made perfect sense, still do.”

“We are the sum of all our decisions, good and bad,” Neff said. “We do not shrink from this. We embrace it. We do not shield our embarrassment. We offer it up. We do not deny any part of who we have been, of who we are.”

The complete text of the plaques and the CACHC’s final report can be found at www.context.olemiss.edu.