Everybody in Harlem knows Satan: The story of Adam Gussow and Sterling Magee

Published 10:30 am Sunday, July 22, 2018

What do a harmonica-playing, three-time Ivy League graduate, suburban New Yorker and a guitar-shredding, philosophizing, anti-establishment Mississippi transplant have in common?

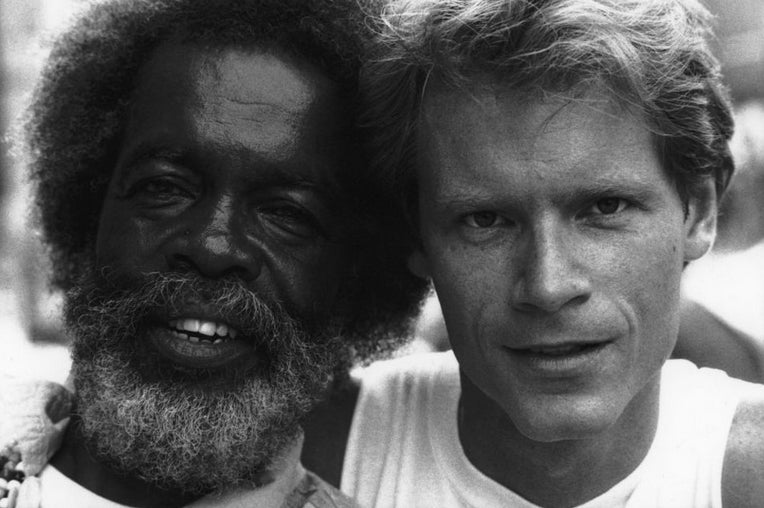

The easy answer would be the Blues. But the former, also known as Adam Gussow, would say it’s more than that. Gussow, a professor at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, is also a world-renowned blues harmonica player and the subject of a new documentary titled “Satan & Adam.”

The film details a 32-year friendship between Gussow and Sterling Magee, a blues player known in the streets of Harlem as Mister Satan. Gussow said he first heard Mister Satan playing on 125th Street, while searching for a quicker way to work.

“I saw this one-man band who was extraordinary. He was 50 years old at that point, and when I asked who he was, people said, ‘That’s Satan. Everybody in Harlem knows Satan,’” Gussow said. “That was the line – I even went home and wrote it down in my journal. I thought, ‘I’m Adam. Satan and Adam need to play together.’ I literally almost conceived of it the way you would in a vision.”

The next day, Gussow returned to the street corner and asked to sit in. He didn’t learn Mister Satan’s real name, or the fact that the bluesman had played at the Apollo Theatre for the likes of James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Etta James and Ray Charles until much, much later.

What he did know, however, was that Mister Satan had a gift like no other.

“He was a triple-threat back in the day,” Gussow said. “He had an original style. He used to say, ‘Mister, you have no idea how hard it is to get your own sound.’”

That style, with its upbeat Harlem street-groove and an ever-so-slight nod to Mister Satan’s Pentecostal Church upbringing in Mount Olive, Miss., paired with Gussow’s Nat Riddles-tutored harmonica style and took the duo to stages across the country and the world.

While playing in Pittsburgh at a club called the Decade in 1995, filmmaker V. Scott Balcerek approached the pair about making a documentary.

“At this point in the arc of our career, we weren’t sure where we were going. So they followed us, they came to gigs and interviewed us privately,” Gussow said. “They weren’t there constantly, though. Then, in 1998, Sterling had a nervous breakdown. He disappeared and I didn’t know where he was.”

Magee’s breakdown and disappearance effectively put the film on hold. It was tough, Gussow said, to go from having two main characters to having one disappear seemingly without a trace. During this time, he admitted he and Balcerek would fight about finishing the documentary. However, they held out because the story simply wasn’t over yet.

Balcerek tracked down Magee, who was staying in a nursing home in Saint Petersburg, Fla., near his family. One scene in the film shows Gussow entering the nursing home where Magee was for a year, but what he finds is a muted version of his mentor. Having lost his ability to play guitar, as well as most of his teeth, Magee held a guitar pick but could barely strum.

However, his condition in that brief period isn’t the way Gussow said he thinks of Magee.

“What I remember is this powerful musician,” he said. “My wife will laugh, because I’ll put on some of our music and listen to what he’s doing. People can copy Robert Johnson’s stuff at this point, but Sterling was more on the level of a Jimmy Hendrix. He was a legend.”

After some rehabilitation, the duo had a small comeback, one in 2004 and then in 2007. What didn’t come back, however, is what Gussow calls the “withering, fast kind of stuff” for which Magee became famous. The one constant, he said, was the distinctive, unhampered voice Magee uses to cut above the music.

After more than three decades of friendship, 23 years of which were captured on film, Gussow said he owes much of who he is to Mister Satan – something he referenced in his book “Mister Satan’s Apprentice.”

“I often say that I was civilized by a black Mississippian. He would prevent me from cursing. Sterling, his whole way, his whole being… you’d never use the word ‘lie’ around him. He’d say ‘You’re telling a story, mister,’” Gussow said. “Sterling had been an Army Paratrooper. He told me stories about being in Germany. He heard there was this guy named Elvis who played guitar, so he found a guy who sold him a guitar, because he wanted to do what Elvis was doing.”

The one question the film, and Gussow himself, tries to answer is why Magee called himself Mister Satan. The explanation is an “overdetermination,” he said, but there’s one explanation Gussow likes best.

Referencing a photo of a young Magee and his wife, Gussow explained that his wife died of cancer, causing Magee to become an alcoholic, curse the heavens and change his outlook on the rest of the world. He wasn’t a satanist by any means, he said, but the name was a paradox in comparison to his actions.

Gussow said he also had a woman break his heart at time, which led to a deeper immersion in the blues.

“He and I found each other in that perfect place where, the pain was still in us, but he was in a positive place. He was also very cynical, and thought preachers were just after the money,” Gussow said. “So he would collect money from the tip bucket he had, and then he would give it away. He’d say, ‘Man, that money’s not for me. The change is what I give out to people.’ It was his collection plate.”

The film succeeds in showing his progressive understanding of this concept, Gussow said.

Because Mister Satan felt like churches didn’t want the street people, he claimed them as his own in a show of pastoral outreach.

“The Satan thing was part of an argument with organized religion,” Gussow said. “He would say outrageous things. He would stand there on the street and say, ‘Why can’t Jesus speak for himself? I’m Mister Satan and I speak for myself.’ It was that kind of thing.”

Gussow now said his life has come full-circle in terms of his experience in the blues. He was brought down to Ole Miss, he said to be the “blues guy,” his dream job.

It’s a long way from his beginnings as the son of two social progressive parents, a Jewish father and Protestant mother, and it’s a chance he admits he could’ve missed.

“If I hadn’t left graduate school – I was out for 10 years – if I hadn’t left Columbia and lived out my musical dreams, none of this would have happened,” he said. “I knew it was the best gig I was going to get.”

To learn more about “Satan & Adam,” which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival complete with a Satan & Adam reunion, visit https://satanandadamfilm.com.