The first invasion of Oxford by Union forces

Published 6:00 am Sunday, January 3, 2016

The first time the Yankees came to Oxford during the Civil War was in early December 1862. As I have related to you in previous columns, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Gen. William Sherman were making their first attempt to capture Vicksburg and gain control for the entire length of the Mississippi River.

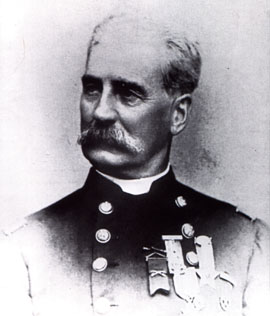

The end of the first invasion came just before Christmas. Grant and Sherman had made Holly Springs the site of their most southern supply depot. Confederate Gen. Earl Van Dorn decided to send some of his mounted troops to make a raid on Holly Springs and maybe drive the Yankees out of Mississippi. This occurred on Dec. 21, 1862 ,and ended the first of the Union forces’ invasion of Mississippi. At this time the Union troops were under the command of Gen. Edward Hatch.

It has been reported the former Congressman Jacob Thompson, attached to Gen. John C. Pemberton’s Confederate forces, was in Oxford at the time the Yankees entered the town of Oxford. In fact, he was on the widow’s walk of Cedar Oaks. At that time, William Turner’s home, later named Cedar Oaks, was where the Graduate Hotel now stands.

As the Union troops made their way into Oxford down North Street (now North Lamar Boulevard), past Ammadelle, a Union soldier shot at a person he spied on the roof widow’s walk of the Turner’s home. Thomspon was not hit and was able to make his way from the widow’s walk to the Confederate forces near Coffeeville.

When Thompson reached the Confederate lines, he made his report to Pemberton on the troop movements into Oxford. It was reported that after Thompson’s report, he made the suggestion to Van Dorn to send troops to raid the Union stores at Holly Springs.

After Grant secured Oxford, one of his first stops was the home of Jacob Thompson. By the time Grant made his way to the Thompson home, his soldiers had already ransacked the house. One of the soldiers on the site of the Thompson home made a report to his commander that they had taken Thompson’s private correspondence dated before the beginning of the war.

The group of letters that were found in Thompson’s private office on the grounds of his 20-room mansion were dated back to 1857 when Thompson was in James Buchanan’s Cabinet.

The letters contained his private correspondence and thoughts on North-South relationships including secession. Grant sent the letters to the Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Stanton then sent the letters to several Northern newspapers for publication.

The letters had reported “Thompson’s treasonable attitudes” and activities prior to the Civil War. Jack Case Wilson in his book on Oxford homes, “Faulkner’s Flames and Fortunes,” writes that Union Gen. Edward Hatch was also on the scene at Thompson’s home. After the town had been secured, Hatch rode from the Square down to Thompson’s home. After dismounting his horse, he made his way into the large home.

Hatch and his men searched the home from room to room. He then had a chair placed in front of the home. Seating himself a large, upholstered rocker, Hatch ignored the pleas of Thompson’s wife to stop his men from ransacking the residence. He refused to stop his men, stating, “Let them go. They can take anything they find, and do anything they want, except take the chair I am sitting in.”

Wilson writes that Hatch soon began to worry about being so far away from the main body of Union forces and he ordered a wagon brought to the front door of the Thompson residence. He then ordered his men to fill the wagon with beautiful oil paintings, silver plates, and china — all stolen from the Thompson home.

This first invasion of Oxford ended without them destroying any homes or the businesses in town. This would occur later in the war in 1864, however, as a parting blow to the residents of Oxford several houses were set on fire but quickly put out after the Union soldiers left Oxford before Christmas. The burning of the town and five houses would not occur until almost the end of the war.

Jack Mayfield is an Oxford resident and historian. Contact him at jlmayfield@dixie-net.com.