Lamar and Grant’s unexpected first meeting

Published 6:00 am Sunday, June 5, 2016

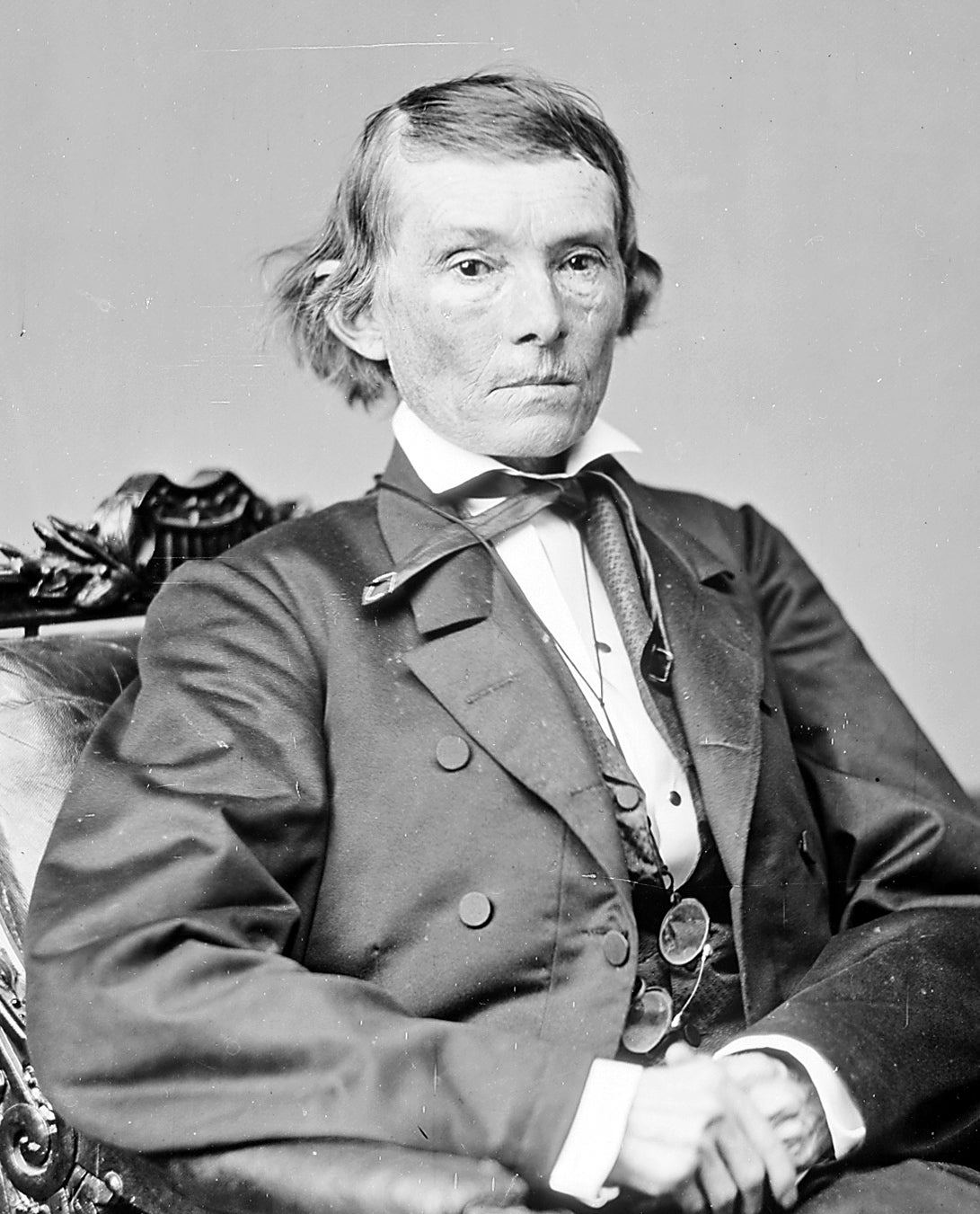

- Portrai

By Jack Mayfield

This week I want to give you a little historical look at the chance first meeting of L.Q.C. Lamar and Ulysses S. Grant. The chance meeting was unexpected and happened just as Lamar was regaining his old seat in the United States House of Representatives. It was also before Lamar made his famous speech upon the death of Charles Sumner.

There was no possibility of the two meeting before the Civil War. Lamar was a former small town lawyer, professor and congressman before the war. Grant was a lowly shopkeeper and “washed up professional soldier.” There was just no way their paths would cross.

During the war, Lamar was only in battle at the very beginning of the war. Grant was then in the west and Lamar in Virginia. Lamar also spent much of the war in Europe. So they would not have met on the battlefield. Although Lamar was in Oxford right before Grant and Gen. William Sherman made their way to Oxford on their first attempt to capture Vicksburg in December 1862, he had left the area to make his trip to the Court of the Czar in St. Petersburg.

One interesting event did happen that involved Lamar’s plantation just north of Oxford and Grant’s march down the Mississippi Central Railroad. Lamar owned a plantation and had a home called Solitude on the property. Lamar’s plantation was north of Abbeville, and just south of the railway river crossing at the Tallahatchie. This meant Grant’s line of march was situated near the railroad and thus near Solitude.

While in Oxford, Grant would learn from the Van Dorn’s raid on Holly Springs just before Christmas Day, that he could get supplies for his men by raiding the area, 15 miles on either side on his line of march. This would mean that Lamar’s plantation home was within that area. Solitude was very near the line of Grant’s march. There is no notation anywhere that I can find that reports any looting by Grant’s men while passing Solitude, but that does not mean it did not happen.

Solitude was abandoned after the war and Lamar would make his home on North 14th Street in Oxford and in Washington, D.C. I am sure that there was some resentment on the part of Lamar on what the Yankees did do on their trips to Oxford.

The chance meeting of the two did not come about until after Grant had been elected president and Lamar had been somewhat “reconstructed” and had his “disability” lifted that allowed him to take up his old seat in the House. The meeting was at the White House and an old friend had brought Lamar to the meeting from the days before the war and during the war.

Alexander H. Stephens had been a congressman with Lamar on the eve of the Civil War. Stephens represented a congressional district in Georgia. During the war he was the first and only vice president of the Confederacy. After the war he was one of the first to have his disability removed and he too took up his old seat in the House. In early December of 1873, Stephens took Lamar to the White House with him for an important meeting. From what I have gathered, neither of the men had expected to see or even meet with the president.

On Christmas Day 1873, Lamar wrote a letter to his friend in Jackson, T.J. Wharton. In the letter, Lamar recounts the meeting with Grant at the White House and gives his friend a candid view of the Republican President. I find it interesting that their paths through history had not caused these two men to meet. They both held very visible places in the history of the middle 19th century.

Lamar states of the meeting that the two men, Stephens and Lamar, were ushered into a reception room and told that the president would be with them shortly.

Lamar writes in his letter, “Soon another person came in, whom I took to be one of the upper servants. He said, ‘Good morning, Mr. Stephens.’ Mr. Stephens to my utter astonishment replied, ‘Good morning Mr. President. Allow me to introduce Colonel Lamar, member of Congress from Mississippi.’

“I had seen his pictures, and had heard A.G. Brown (a former Senator from Mississippi) describe him, but I was taken by surprise. He is, at first sight, the most ordinary man I ever saw in a prominent position. He is about the complexion and size of _______.” (For some reason my source, Edward Mayes’ biography, for this comment put a blank instead of the word. I guess he wanted the reader to decide what or whom he was the complexion and size of.)

Lamar did go on to state that Grant, “talked freely in a voice not very deep, but with a slight rasp in it, such as you sometimes observe in men who drink a great deal.”

He also used a French term to describe the president. He stated of Grant, “after scanning him closely you see before you a very strong, self-contained man, full of purpose, resolute even to obstinacy, and of infinite sang-froid.” President Grant was “cold blooded?”

Lamar goes on in his letter to his friend back in Mississippi, that he feels Grant may have been all these things, but he did not lack a conversational power. He may have had a narrow range of ideas, but he was “the most ambitious man that we haven ever had. His schemes are startling.”

I think one of the most telling remarks that Lamar makes in the letter gives you a clear idea that he dislikes Grant. Lamar is quoted as stating, “With all the emissaries, spies, employees, and tools that his patronage gives him, there will be no limit to the despotic power which he is ever ready to use relentlessly and fearlessly for his own purposes: which purposes are the most arbitrary that have ever yet been cherished by a Federal Executive.”

I am sure that Lamar was thinking about his home state and the fact that it had not yet been redeemed from “Carpetbag Rule.” Adelbert Ames and Grant’s brother-in-law, Louis Dent, were in power back at home.

Mississippi would not be fully reconstructed in 1873 but by 1877 Lamar had helped engineer a compromise that brought about the end of military occupation in the South.

Jack Mayfield is an Oxford resident and historian. Contact him at

jlmayfield@dixie-net.com.