The Vagabond Professor

Published 6:00 am Sunday, August 14, 2016

By Jack Mayfield

Last week, I wrote about an early professor, Edward C. Boynton, who came to the new state university at Oxford who had also attended West Point.

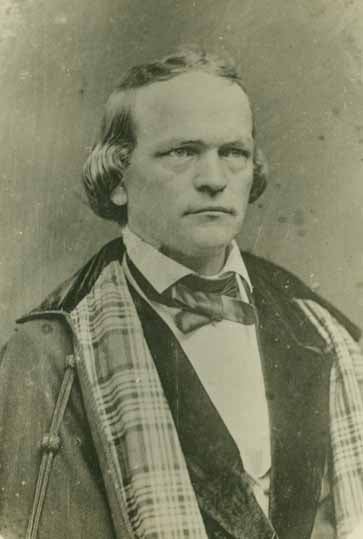

This week I want to give you a little information on the second professor employed in 1849 by the new state university, Albert Taylor Bledsoe. He also had a West Point connection, but unlike Boynton, his sympathies went to the South and the “lost clause.”

Bledsoe was born in Frankfort, Kentucky in 1809. He graduated from West Point in 1830 and was a classmate of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee. Upon graduation in 1830, Bledsoe was commissioned a second lieutenant and was sent to the frontier and to Fort Gibson in the Indian Territory. He did not want to make the military a career and resigned his commission in 1833. This began the movement from position to position for a number of years.

Over the next few years he read for the Law with his maternal uncle in Richmond, Samuel Taylor; he tutored mathematics at Kenyon College in Ohio; then he became interested in theology and became a Protestant Episcopal minister; then he became professor of mathematics at Miami University in Ohio; then he was the Rector of churches in Sandusky, Hamilton and Cincinnati, Ohio; then he was assistant to the Bishop of Kentucky.

Finally, he decided he should get out of the ministry and he moved to Springfield, Illinois and began to practice law. This is where his movements crossed paths with a man that would become president of the United States — Abraham Lincoln.

While living at the Globe Tavern in 1843 and 1844 with his wife, Lincoln and his wife were also living at the tavern. When Mary Todd had her son, Robert, Mrs. Bledsoe aided her in the care of her infant son.

At this time Bledsoe saved Lincoln from a duel by unusual means. James Shields had challenged Lincoln, and Bledsoe was to be his second. They argued and Bledsoe won and they to use broadswords as their choice of dueling weapons. The duel never took place. Bledsoe would leave Springfield in 1844 and go again to Cincinnati. He would practice law in Washington before going back to Springfield in 1847.

While in Springfield, he received word that he had been elected to the faculty of the new state university at Oxford. He moved to Oxford in 1849 and began to teach mathematics and astronomy, and later natural philosophy. A young L.Q.C. Lamar was put on the faculty to ease the workload for Bledsoe and they became friends because of their shared interest in metaphysics.

If you will recall, George F. Holmes didn’t remain on campus very long in his position as president of the new state university. After Holmes departure, the Board of Trustees made Bledsoe the acting head of the university until Judge Augustus Longstreet could make his way to Oxford. Bledsoe was instrumental in getting the student body under control. He also became the first professor at the University of Mississippi to have a work published while teaching at the university.

In 1854, Bledsoe would leave the University of Mississippi for the University of Virginia. Before he left Oxford, the university would bestow on him the first honorary degree from the university. He was given a Doctor of Laws. I found one thing that was interesting about Bledsoe’s tenure at our university, his friendship with Lamar. He is quoted as stating that he taught Lamar everything he knew, especially how to think.

After the Civil War, Bledsoe became the prototype for an “un-reconstructed Rebel.” He spent his considerable talents defending the “lost cause.” In 1866 he published “Is Davis a Traitor, or was Secession a Constitutional Right Previous to the War in 1861.” Davis’ chief consul would state that without the facts from this publication, he could not have saved Davis’ life.

Bledsoe would again become an ordained minister, this time, the Methodist Episcopal Church South. He would become the editor of the Southern Methodist Church’s official publication, the “Southern Review.” This would be Bledsoe’s last position and his moving would cease in 1877 when he died.

Dr. David Sansing makes a great point in his history of Ole Miss about Bledsoe. He states, “In 1877, at the end of his long and exciting life, professor Bledsoe could claim that he had served as Abraham Lincoln’s second, taught Lamar how to think, brought Holmes out of exile, and saved the life of Jefferson Davis.”

Jack Mayfield is an Oxford resident and historian. Contact him at jlmayfield@dixie-net.com.