Sky-high hospice discharge rates point to fraud

Published 10:19 am Monday, October 24, 2016

By Larrison Campbell

Mississippi Today

More Medicare beneficiaries leave hospice care alive in Mississippi than in any other state in the country, an indication of the state’s ongoing problems with Medicare fraud, according to government officials.

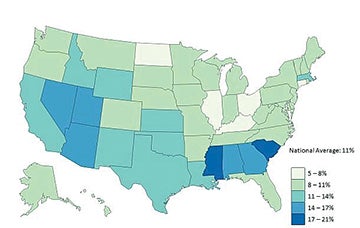

In 2014, Mississippi hospice providers discharged 20.6 percent of their Medicare patients alive, according to data released last week by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. In South Carolina, which ranked second in live discharges, 18.3 percent of Medicare patients were discharged alive. The national average is 11 percent.

“Mississippi has an epidemic of hospice fraud,” said Chris Covington, an assistant special agent for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General, who has been investigating Medicare hospice fraud in Mississippi since 2013.

In a perfect world, the live-discharge rate for hospice, which provides end-of-life care for terminal patients, would be zero. Of course, death is not always predictable, and some errors are expected, say hospice advocates.

But Covington said discharging one in five patients alive indicates that many of Mississippi’s hospice providers have been billing Medicare for services that their patients never needed.

“I can think of absolutely no reason to explain the high live discharge rate other than the fact that these patients never even belonged on hospice,” Covington said. “That’s why these patients get discharged alive, because they weren’t dying in the first place.”

There is precedent for fraud among hospice providers in Mississippi. Since 2014, the U.S. Attorney’s Office has arrested or indicted nine people in hospice schemes that defrauded Medicare of nearly $15 million dollars. So far eight have pled guilty. Government officials say more are likely.

“It’s big figures, lots of money. … And it’s still a problem,” said Chad Lamar, assistant United States Attorney for the Northern District of Mississippi.

“More indictments? Absolutely guaranteed. Put all your money on black; it’s going to pay off. We are aggressively pursuing hospice fraud in the state of Mississippi. And the project is not done,” Covington said.

An “incestuous” system

Each scheme follows what Covington calls a “cookie cutter pattern.” The hospice owner will generally contract with a runner, who is paid via salary or kickbacks, to go door-to-door and find Medicare beneficiaries to enroll in their hospice programs. They’ll often sweeten the pot with incentives like $50 gift cards, selling the program as a way to get free housekeeping and weekly visits with a nurse. What they don’t do is mention that Medicare’s hospice program is, by law, reserved for the terminally ill.

Most patients are shocked when they find out that hospice is solely for patients with less than six months to live. They’re also shocked, he said, when they find out how much their hospice providers have billed Medicare.

“We literally see instances where Medicare has paid (up to) $35,000 in benefits in hospice, and the patients immediately say, ‘Well, they just come by and clean the house’ or, ‘they just come by and take my blood pressure,’” Covington said.

“When you’re caring for the terminally ill, the expectation is the services you’re providing are very involved, and in these cases because the patients are not terminally ill, Medicare isn’t really paying for what it gets.”

The final step in the process, according to Lamar and Covington, is the terminal diagnosis. In order to qualify for Medicare, a doctor needs to certify that a patient has less than six months to live. But rather than ask a patient’s typical physician, runners bring patients to the hospice provider’s medical director, who then signs off on the terminal diagnosis, usually without the patient’s knowledge. In the case of Dr. Walter Gough, Jr. of Drew, the incentive was a financial kickback of $14,000 a month.

Gough’s case illustrates a typical hospice fraud scheme, according to Lamar. Gough was hired in 2010 by Andre Kirkland, the co-owner of Revelation Hospice in Cleveland. His wife, May Gough, was hired as the runner, at a fee of $4,000 a month. Court documents show that between 2011 and 2013, the Goughs helped Kirkland steal millions of dollars from Medicare. At the time of Kirkland’s arrest, Revelation had a live discharge rate of 93%.

Last month, Kirkland was sentenced to 48 months in home confinement and ordered to repay Medicare nearly $5.5 million. Walter Gough died unexpectedly before entering a plea. May Gough pled guilty but has not yet been sentenced.

Another runner, Patrick Pendleton, recruited patients for at least five different hospice providers throughout the Mississippi Delta. He pled guilty to Medicare fraud in May and was sentenced to 40 months in prison.

Lamar said employee overlap like Pendleton’s is why this type of fraud has proliferated in Mississippi, specifically the Mississippi Delta. As was the case with Andre Kirkland, who was a nurse before opening Revelation in 2009, many fraudulent hospice owners learned to commit fraud while working for other hospice providers.

“There’s a lot of incestuous relationships between the hospice providers that we’ve charged (with fraud). It’s common to see employees switching from one to another, patients being switched from one to another. And doctors willing to engage,” Lamar said.

Mississippi’s alarming numbers

Covington describes many of these hospice programs as small “mom and pop” operations, and the ease with which they crop up stands out when looking at the numbers of providers in the state. In 2015, Mississippi had an average of 65.1 hospice providers for every 10,000 hospice beneficiaries, according to data provided by the Department of Health and Human Services. The national average that year was 31.3.

A total of 108 hospice providers operated in Mississippi in 2014, which is the 12th highest number of providers in the country, according to the CMS data. But Mississippi ranks 31st in population. Every state with more hospice providers also has a larger population. California, which had 499 hospice providers in 2014, is 13 times the size of Mississippi. Florida, the fourth most populous state, had only 42 providers.

And Mississippi’s high live discharge rates aren’t the only numbers that point to fraud, according to Covington. Another metric is the number of patients who spend more than 180 days in hospice. When a doctor certifies that a patient is terminally ill, Medicare automatically approves them for a six-month stay in hospice which can be reassessed and extended. Patients who aren’t terminally ill tend to live well beyond the six-month window of care. In Mississippi’s case in 2014, that was 2,574 of 15,004 patients.

Mississippi ranked third in duration of hospice stays, with 17.2 percent exceeding 180 days. Only Alabama (18.4 percent) and South Carolina (18.1 percent) ranked higher, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data.

Mississippi’s numbers alarmed even members of the hospice industry who had not been tracking the fraud investigations. Joy Cameron, vice president of policy and innovation at the Visiting Nurse Associations of America, said Mississippi’s numbers concerned her enough that her organization had reached out to the Centers for Program Integrity within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services about doing a strategic data-based targeting of hospice providers to examine whether they have been providing the appropriate care.

“We don’t want this whole industry to get painted with a broad brush, but we want to help them strategically find those who are the bad actors in our industry who are giving us all a black eye,” Cameron said.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services would not say whether such conversations had taken place, but they did confirm the correlation between high rates of live discharge and fraud.

“Many hospices believe longer lengths of stay and high live discharge rates reflect the changing population of patients seeking hospice care. Through Medicare’s program integrity data analysis of health services and benefits at this level of care CMS believes that, in some instances, these same factors may be indicative of fraudulent activities meriting investigation,” CMS officials said in an emailed statement.

Some hospice advocates agreed with CMS and said that cultural factors can also contribute to high live discharge rates.

In communities with higher rates of poverty and lower levels of educational attainment, people may be less familiar with the concept of hospice, according to Jamey Boudreaux, executive director of the Louisiana Mississippi Hospice & Palliative Care Organization. As a result, when a loved one nears death, family is more likely to call for an ambulance or rush them to the hospital. If a patient is transferred from hospice to a hospital, even if it is hours before death, they are marked as a live discharge.

Still, Boudreaux said he found the numbers disconcerting enough that his organization will be launching a “deep dive” into the state’s hospice data in search of an explanation.

“It took us a little bit by surprise. We knew there were some high live-discharge rates in Mississippi; we didn’t realize it was the highest in the country,” Boudreaux said.