Letter to the EAGLE marked passing of local church

Published 6:00 am Sunday, January 15, 2017

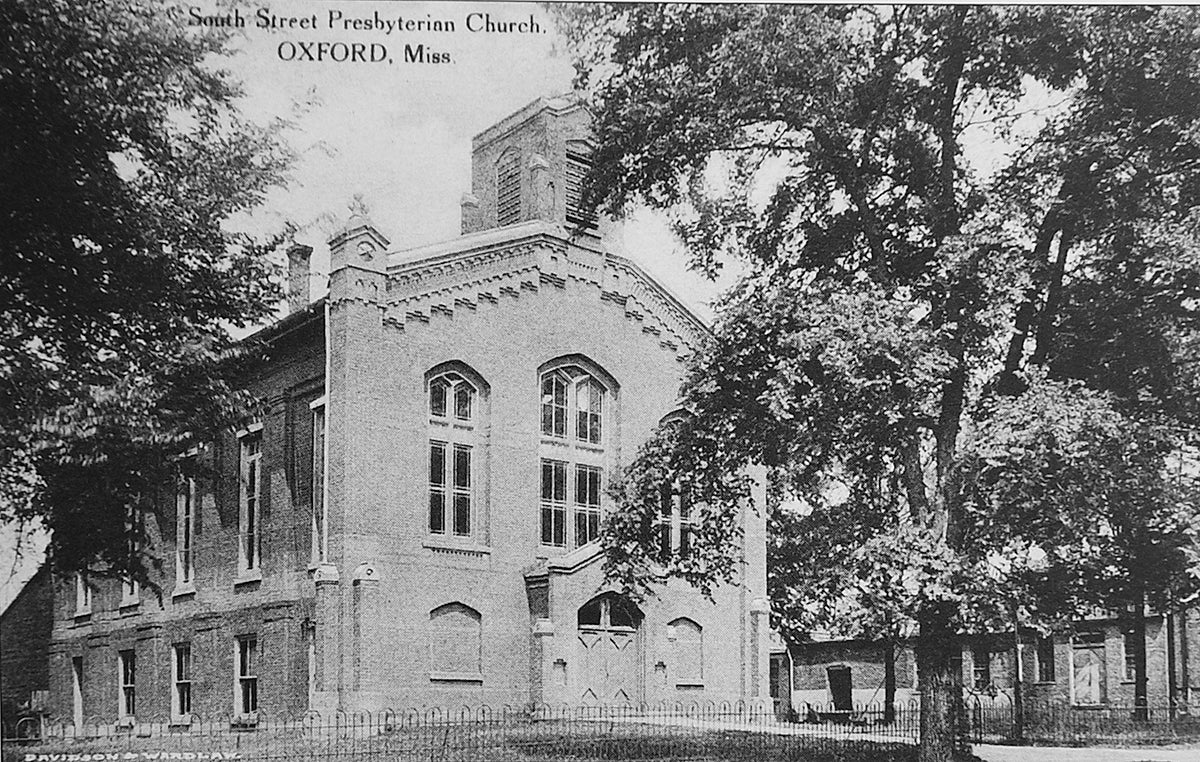

- The Cumberland Presbyterian Church, also known as South Street Presbyterian Church, was considered by many to be the most beautiful church in Oxford.

By Jack Mayfield

This week and next, I want to write about a church in Oxford that survived the burning of Oxford by the Yankees on Aug.22, 1864, only to be torn down in 1941 to make way for “progress.”

The wrecking ball has claimed many old structures here in Oxford and luckily the citizens have instituted a preservation commission that has stopped the loss of important and historical sites around our “little postage stamp of native soil.”

The First Cumberland Presbyterian Church was built around 1837 on the east side of the Square. It was a log building that was replaced in the 1840s by a brick church. This church burned in the early 1850s and a new church was built on the large lot just off the Square between Harrison and Tyler. The church faced east on South (Lamar) Street.

The new church building was designed by Henry Worley and was very similar to the Lyceum on the University of Mississippi campus. It had six Tuscan columns across the front in the Greek and Roman style, a combination of Greek and Roman architectural elements. The only known photograph of the church building, as it looked in 1864, is one showing the ruins of the Oxford Square after the burning. The photograph is with today’s column and the building can be seen in the upper left-hand corner.

In January and February of 1941, the owners of the property decided it was time to remove the building to make way for a block of buildings and a parking lot. Today the block of buildings runs from Soul Shine to Landry’s. Both William Faulkner and his brother, John, wrote about the old Cumberland Presbyterian Church between Harrison and Tyler on South Lamar, and they lamented over the loss of the church. John Falkner was the first to write about the church in a letter to the EAGLE on Feb. 6, 1941.

“They tore down the old church down. They knocked the hand-forged pins from the hammered hinges and let the tall arched windows fall into the vestibule, then dragged them out into the yard and stacked them against the grillwork of the iron fence. Next they ripped the pews loose from the floors and you could see where their high backs had been worn soft and smooth and ageless with the thin kneeling hands of faith and high hope, and then just courage, and perhaps a dry tear squeezed from gentle eyes that had looked, too long into the North where Jackson, Lee, and Stuart rode.

“You could stand in the inner door beneath the axe-hewn timbers that supported the gallery in which the slaves sat and worshiped and look down the long emptiness beneath the cross-timbered dome ad before they tore out the leaded windows with their age-old promises stenciled in colored glass, you could see the sunlight filtered in bars of blue and red and yellow pick the lost dreams from swirling dust motes above disturbed floor. Blue for the faith and quiet hopes that outlasted four years of hunger and cold and disaster, red for the hot courage that placed the barred flag clutched in a dead hand in the mouth of the Federal cannon of Gettysburg, and yellow for the tasseled sashes above the slim gray waists beneath the hawk-like eyes and taut cheeks that rode with Van Dorn around Grant’s flank into Holly Springs in desperate sally and routed the hopes of a nation one afternoon.

“They pryed the dry heart-timber of the window casements out in long silvers and as leaded panes fell, a shaft of sunlight pierced the calm dust beneath the pulpit where, the girl in hooped-skirt and beribboned pantalettes had stood with flag clasped in demure hand while full timbered, resonant voice had blessed and consecrated the bright new folds and the tasseled, golden cord and the tall staff tipped with the spread eagle in permanent brass. And the gallant gray figure had knelt in the massed hope of ten hundred eyes and taken the flag as a symbol and an accolade and perhaps touched the shy hand in the taking.

“The roof was torn off and flung aside and the firm truths and full-voiced hymns that had rung in its vaulted dimness for a century and four years were released at last into the infinite blue from whence they had come. They laced steel cables through the sightless windows and sliced the cables through patient walls with drawn tractors and the voiceless brick shattered in tumbling resignation and above the still, pastel-tinted cloud of their dissolution arose the new church, wraith-like and soft azure flowing, steadfast as it Holy benediction and as fragile and imperishable as the memory of a dream.”

I trust that you readers do not mind that I have written John Falkner’s entire letter to The EAGLE. There is no way I could have paraphrased his comments on the demolition of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, “the most beautiful church in Oxford.” Falkner’s reference to the regiment flag dedication ceremony at the church in 1861 is when the University Greys and the Lamar Rifles readied for action during the Civil War.

I wanted to give you a sense of what this building looked like from an artist and writer’s point of view. This is just one of the many buildings and homes around Oxford that have been lost to “progress” and that has been going on for a long time. We need to stop and look around. Do we want someone like me writing about something we only have a few words written about and maybe a few old grainy photographs?

Next week a little more of the history of “Oxford’s most beautiful church” and its demise and demolition.

Jack Mayfield is an Oxford resident and historian. Contact him at jlmayfield@dixie-net.com.