Drug Court grads turn lives around

Published 10:49 am Wednesday, February 15, 2017

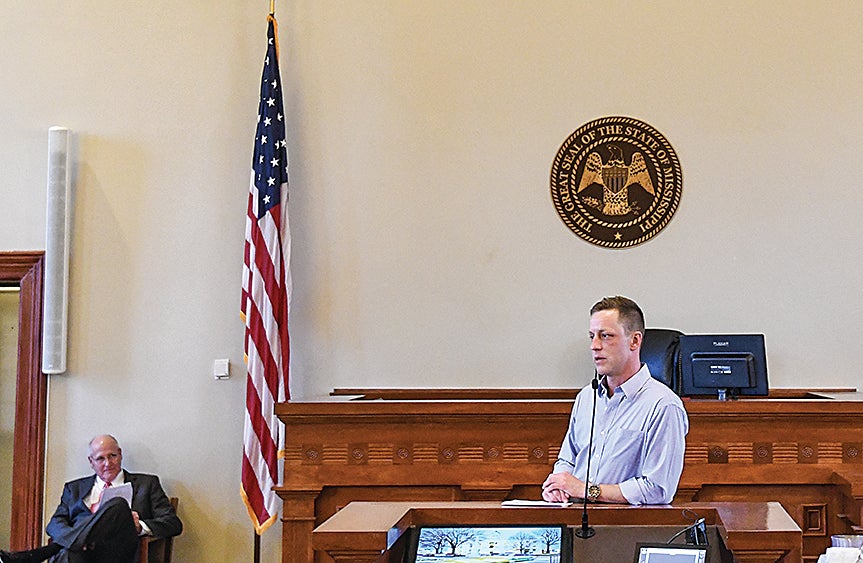

- Brian Adams speaks at the Third Judicial District's Drug Court graduation, at the Lafayette County Courthouse in Oxford, Miss. on Tuesday, February 14, 2017.

Three years ago, Stephanie’s life was a mess.

“Addiction had taken over me to where I didn’t know myself,” she said Tuesday, moments before graduating from the Third Judicial District Drug Court.

Her children were taken away. She was facing serious criminal drug charges. She tried a 30-day in-patient program but relapsed a week later. She was placed into Drug Court, which became a life-changer for her — but not without a lot of hard work, frustration and moments of triumph.

“The first year of Drug Court, you’re trying to find yourself,” she said. “The second year, you’re still adapting to being sober but by the third year, it becomes a lifestyle.”

Today, she has full custody of her children, her first “real home,” an associate’s degree and full-time work as a caregiver.

“I could not have made it this far with the support of my family, friends and especially God,” she said.

Stephanie, who requested not to use her last name, was one of a dozen Drug Court participants who graduated from the three-year-long program Tuesday.

Eight other program participants who are nearing completion of the program’s requirements were recognized during the ceremony, said Drug Court Coordinator Brandon Vance. Those eight participants are expected to fulfill all their obligations for graduation by May 19.

Each participant must spend at least three years under the supervision of the Drug Court and comply with all program requirements before being eligible to graduate, which includes regular drug testing, mandatory counseling and addiction recovery meetings.

Circuit Judge Andrew K. Howorth presided over the ceremony.

Rebuilding trust

Guest speaker Rod Farrar, clinical director of Stonewater Adolescent Addiction Recovery Center in Oxford, quoted from Ephesians 2:1-10, which speaks of being made alive again by the grace of God.

“That any of us changed from a life of addiction to recovery is only through the grace of God,” he told the graduates.

Farrar, who has been sober for 18 years himself, said rebuilding trust with family and friends is one of the hardest, yet most rewarding steps of sobriety.

“We know what it’s like to get the keys back from our families because they trust us again,” he said. “Trust is a difficult thing to come by.”

He said when people who don’t struggle with addiction make comments that they can’t understand how addicts can do some of the things they do, he asks them what lengths they would go to feed their child if he or she hadn’t eaten in three days.

“If you love something, you would do whatever necessary to protect it,” he said. “Unfortunately, we as addicts loved an inanimate object more than we loved anything else. But here you are today, clean and you’re clean for a reason, and that reason may be the person you come across tomorrow. Your paths may cross with someone telling a story similar to yours, asking how are they going to get through this, and you’ll tell them how you did it.

“Your pain and your trials won’t be in vain.”

The Third Judicial District Drug Court currently has 245 participants from Lafayette, Benton, Calhoun, Chickasaw, Marshall, Tippah and Union counties. Due to the large size of the program and the distance that participants must travel, a second Drug Court office was established in Ripley. Howorth supervises participants assigned to the program in Oxford, and Circuit Judge Kelly Luther supervises the group in Ripley.

Drug courts seek to rehabilitate drug-using offenders through drug treatment and intense supervision with frequent court appearances and random drug testing. Drug courts offer the incentive of a chance to remain out of jail and be employed and the sanction of a prison sentence if participants fail to remain drug-free and in compliance with all program requirements.

Brian Adams also graduated Tuesday. He said more than three years ago he was just about homeless in Oxford when he was arrested in the driveway at his parents’ home. He had left Haven House, robbed several bottles of alcohol before finding his way to their home. There his mother had spoken the words that would lead him on his path of recovery.

“She told me if I wanted to kill myself, she would pay someone to do it just to get it over with because she couldn’t stand seeing it being done slowly,” he said, his voice cracking with emotion.

Today, Adams is working on his doctorate degree at the University of Memphis.