Mississippi has an $89M Medicaid issue

Published 9:52 am Monday, March 13, 2017

By Larrison Campbell

Mississippi Today

When James Huffman, who runs Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto in Southaven, looks at his hospital’s budget, he knows he’ll have to make cuts this year. He’s just not sure where to make them.

“I have to clean rooms. I have to prepare meals. I have to have nurses to take care of patients. I’ve got to have pharmacies. I’ve got to have respiratory therapists,” Huffman said. “… I’ve got to find a way to make payroll every two weeks, and if Medicaid payments suddenly stop, I can’t.”

Medicaid is one of Baptist-DeSoto’s biggest insurers, covering more than 10 percent of its patients. And right now the state agency is at a crisis point, facing a near record-breaking $89 million budget deficit.

So far this session, lawmakers have committed only to fulfilling about half that deficit. This means Huffman and other hospital CEOs statewide will face their own budget crises and risk eliminating some patient services.

If Medicaid, a state agency, can’t close the deficit with internal cuts, state code mandates Mississippi’s providers step in and cover up to $40 million of the losses through a series of provider cuts. This includes a maximum $10 million tax assessment on all 110 hospitals in the state.

“It puts me in a position to be a tax collector for the state, and the only other people paying the tax are sick people,” Huffman said. “So if the tax goes up, the only way I can come up with another dollar to pay the state is to not provide certain services. Medicaid patients only pay the cost of the services we provide. There’s no profit margin built in.”

Medicaid explodes

In the past decade, Medicaid’s budget has ballooned to over a billion dollars, even as the number of recipients has fallen. That, combined with an appropriations shortfall and three rounds of state-wide budget cuts, has left the agency $89 million in the hole for 2017.

Medicaid is a notoriously difficult agency to trim internally. Like an insurance company, the bulk of the budget — 97 percent — goes toward health care services such as doctor visits, tests and prescriptions. This means the agency could cut all 900 employees and close all 30 regional offices, and the $30 million savings still would not fill the deficit.

Medicaid officials are waiting to see how much the Legislature’s deficit appropriation ultimately totals before they say whether they will need to implement the hospital tax and other cost saving measures. But Erin Barham, the agency’s deputy administrator for communications, admitted the agency will have a hard time closing the $45 million hole on its own.

“That’s why we’re taking a wait and see approach,” Barham said. “Because it’s true, even if we cut all of our people it wouldn’t make up for everything.”

Gap not closing

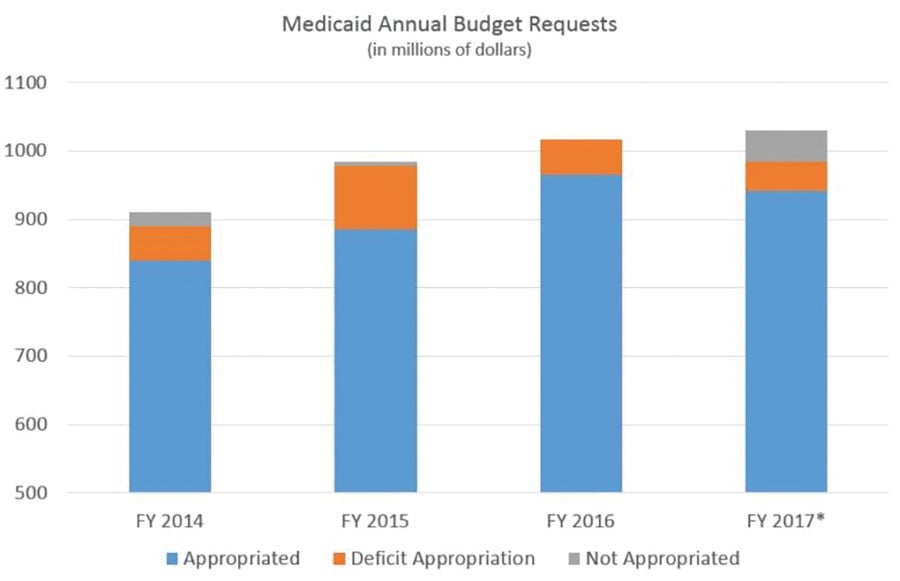

Deficits are nothing new for the beleaguered agency. Each of the past four years, the Legislature’s initial budget appropriation has fallen tens of millions of dollars short of Medicaid’s request.

What is new is that this year, the Legislature has not committed to closing the gap. When Medicaid faced a $51.6 million shortfall in 2016, the Legislature approved a deficit appropriation for the full amount. The year before, when Medicaid announced a $99 million deficit, the Legislature came through with $92 million.

This year, the proposed appropriations are far less: $40 million and $43 million from the House and Senate, respectively, meaning as a best case scenario, the agency still will be short $45 million. The Legislature has until March 14 to vote on these bills.

Legislators point to Medicaid’s paradoxical rising costs and falling beneficiary numbers as examples that the agency needs to rein in its costs. But in the meantime, many in the hospital community say they feel caught in the middle, which begs the question: Is it really a Medicaid cut if private hospitals have to foot the bill?

“It’s not fair, particularly to the patients, and it’s not fair to the providers to take these cuts,” said Richard Roberson of the Mississippi Hospital Association. “When a provider has to pay taxes, that’s additional resources they can’t invest in their business. It’s money they can’t use to hire clinics and staff, upgrade technology, improve facilities or upgrade infrastructure — and all these improvements improve the patient’s experience within these facilities.”

Medicaid’s enrollment hit a peak in March 2015 and has steadily declined since, a trend the agency largely attributes to beneficiaries not complying with annual renewal requirements. Meanwhile, the agency’s budget has continued to rise, from $985 million in 2015 to a projected $1.03 billion for fiscal year 2017.

Legislators skeptical

In budget hearings through the fall, Dr. David Dzielak, the agency’s executive director, attributed much of Medicaid’s cost increases to two things: additional mandates imposed by the Affordable Care Act and skyrocketing medical inflation. But many legislators remain skeptical that Medicaid has so little control over its costs.

“The facts, based on Medicaid’s own numbers, are that enrollment numbers are going down and costs are going up — to the tune of one billion dollars this year. That’s not sustainable,” said Sen. Brice Wiggins, R-Pascagoula, who chairs the Medicaid Committee. “We’re in this together. From providers to legislators to the managed care companies.”

Regardless of whether providers want to be roped into Medicaid’s debts, they’re currently bound by state code. These rules say that if Medicaid has a deficit the executive director can appeal to the governor to declare a financial emergency. This imposes two rounds of cuts. The first is to cut coverage of at least one “optional service.” Prescription drugs and certain tests and types of care, such as hospice, fall into that category.

State code then mandates that Medicaid reimburse providers at a reduced rate, up to $40 million dollars. For hospitals, this comes in the form of an additional $10 million tax assessment. If this still doesn’t fill the deficit, Medicaid can impose additional provider cuts.

The irony, according to some, is that this policy of relying on businesses to cover a state agency’s budget hole exists in a state that prides itself on low taxes.

“It seems somewhat antithetical when the precedent has been established over the last few years for decreasing taxes on folks, rather than increasing them,” Roberson said. “So I don’t know why that would be different for health care, where there is such a strong need and such valuable services are provided.”

Wiggins, for his part, told Mississippi Today that he had not heard that specific complaint before and said he was “always game for finding out how we can help providers lower their taxes.”

“Providers obviously always want the maximum reimbursement and that makes sense because if you want to treat the patients, you need to be compensated,” Wiggins said.

Tough decisions

The idea of an additional $20 million assessment is a sore subject for many in the hospital community because Mississippi’s hospitals already pay a $300 million Medicaid tax each year, which is used to increase the federal match. Mississippi has a federal match rate of three-to-one, the highest in the country, which means that the hospitals’ $300 million dollar contribution ultimately generates an additional $900 million in state Medicaid dollars. This then goes back to hospitals and other health care providers in the form of reimbursements.

“To the extent that up to ($10 million) can be shifted to providers, it is a provider cut. Well, we’re already on the hook for $300 million, so is that fair?” said Evan Dillard, CEO of Forrest General in Hattiesburg. “It’s been done for a number of years. So it kind of begs the question, ‘Why do you have $300 million coming from providers instead of the state?’”

Wiggins, for his part, said he would like to see several of Medicaid’s services trimmed as a way to rein in the budget, though he declined to specify which ones.

“We as a state provide more services than are required by the federal government,” Wiggins said, noting that the Legislature decides what Medicaid covers. “So are we prepared to make these changes?”

In the meantime, Huffman said he will continue holding his breath. The downside to being the biggest hospital in area, he said, is that if Baptist-DeSoto cuts services, they disappear from that part of the state.

“There aren’t other hospitals to provide what we provide,” Huffman said. “But I’m going to be extremely cautious about doing anything that’s going to reduce quality of care.”